Rehabilitation vs. Incarceration: Rehabilitation in the Criminal Justice System

Drugs of abuse—including heroin, cocaine, and amphetamines—are illegal. Others—including marijuana and prescription drugs—could be considered illegal depending on where the user lives and whether or not the use has been sanctioned.

Drugs of abuse—including heroin, cocaine, and amphetamines—are illegal. Others—including marijuana and prescription drugs—could be considered illegal depending on where the user lives and whether or not the use has been sanctioned.

People caught selling illicit drugs almost always face some kind of legal action, but buying, holding, or taking these drugs can also trigger legal actions. That means people with addictions can and often do get arrested due to their addictions. They may be arrested in their homes in front of their children. They may face an arrest in public in front of strangers, or there may be a traffic stop that ends with a ticket and a summons to court. That court date could end up with a sentence.

To stop that cycle of use and arrest, people with addictions need treatment. When addictions are handled in the right way by professionals, they can and do abate.

People who have been arrested often face two very different treatment venues. They can get the help they need in the community through a treatment program, or they can head to prison or jail, where treatment should be provided. There are pros and cons to each of these addiction treatment venues. Understanding the differences and the similarities is useful for families in this situation.

Exploring the Link Between Addiction and Incarceration

Drug abuse and addiction often go hand in hand. The Prison Policy Initiativereports that, in 2017, one incarcerated person in five faced a drug charge. Of those people, 456,000 were held for a nonviolent drug offense, including possession.

Drug abuse and addiction often go hand in hand. The Prison Policy Initiativereports that, in 2017, one incarcerated person in five faced a drug charge. Of those people, 456,000 were held for a nonviolent drug offense, including possession.

While some charges come with very long prison sentences, the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law reports that most possession sentences are longer than one year.

These two statistics suggest that people head to prisons and jails quite frequently due to their addictions, and once they are incarcerated, they stay incarcerated for a long period of time.

In theory, this should be an ideal space in which to treat an addiction, but the reality is a little more complicated.

Prison Based Drug Treatment Programs

When people enter the prison system, they are examined by a medical officer. This examination helps the staff understand the conditions for which the person needs treatment. The exams also offer a layer of protection for prison staffers. Someone who has a condition on intake cannot later claim that the condition began due to the incarceration.

An intake exam should help to spot an active addiction. After all, people who take drugs like heroin often experience very visible withdrawal symptoms, including:

Opioids aren’t the only drugs that cause withdrawal symptoms. People with a longstanding alcohol abuse problem may experience hallucinations upon withdrawal, seeing things that aren’t there and speaking to people others can’t see. If left untreated, this form of withdrawal can lead to seizures. These seizures can be treated with medications, but the medications must sometimes be given for a long period of time. When the medications wear off, the seizures may return. That often means people in medical detox from alcohol need around-the-clock monitoring and care.

Even though these withdrawal signs may be obvious, and they should indicate a need for both medical detox and followup rehab counseling, people who have been incarcerated don’t always get the help they need.

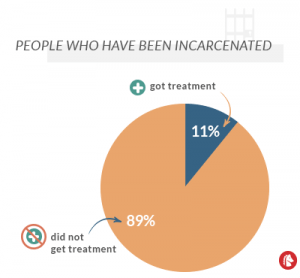

Research cited by the American Public Health Association suggests that only 11% of people who have been incarcerated and have addictions get treatment for their addictions. The rest are simply incarcerated with the hope that their addictions fade away as the time ticks by on their sentences. They may be given absolutely no treatment at all, either during withdrawal or during recovery, or they may be given such small and tiny amounts of care that it amounts to getting no care at all.

Research cited by the American Public Health Association suggests that only 11% of people who have been incarcerated and have addictions get treatment for their addictions. The rest are simply incarcerated with the hope that their addictions fade away as the time ticks by on their sentences. They may be given absolutely no treatment at all, either during withdrawal or during recovery, or they may be given such small and tiny amounts of care that it amounts to getting no care at all.

It’s hard to overstate how damaging this can be. People who are physically ill due to withdrawal can lose their lives as their brain cells and body cells adjust to the lack of the substances they once took. Once withdrawal is complete, these people may struggle with cravings for drugs that are overwhelming and difficult to manage without professional help. They may not have the coping skills to help them deal with their cravings, since they have had no form of therapy. Drugs can, and often are, available in prisons. Without therapy, people can keep using in prison.

When prison addiction programs are designed and implemented well, according to the Federal Bureau of Prisons, they can bring about amazing benefits. The bureau says people who emerge from these programs cause fewer problems while in prison, and when they are released, they tend to avoid recidivism.

When describing a program used to treat people in prison, the bureau outlines counseling programs that utilize cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). This therapy helps people to change the way they think about the world, as well as they way in which they react to their world, and that can have a huge impact on reducing relapse.

The bureau also discusses a residential program in which people with addictions live together and participate in group counseling as well as vocational activities. They learn from one another, and they develop skills together. Programs like this can help people understand how to relate to the people they meet each day.

These are the sorts of therapy techniques that wouldn’t be unusual in the private sector. But unfortunately, these aren’t techniques that are used in all prisons.

An opinion piece in The New York Times outlined treatment conditions in Kentucky jails. The author suggests that incarcerated people simply languish while they wait for their sentences to end. The only treatment they see involves an infrequent visit from an Alcoholics Anonymous volunteer. This simply cannot be considered a comprehensive addiction treatment program.

Giving people the right therapy at the right time matters. In a study of young people, published in the journal Criminal Justice and Behavior, researchers found that addressing a person’s specific needs with treatment significantly reduced recidivism rates. When people get the help they need within the justice system, they tend to avoid committing more crimes that would land them back in prison or jail. This kind of treatment, which is tailored to the person in need, does work.

Treatment like this can be expensive, however. While federal prisons may have deeper pockets to draw on in order to provide care to prisoners, state-run facilities may not have the same large budget to help them provide care. Federal prisons may also face more oversight from legislators and the community at large, so they may feel pressure to provide care that is exceptional and beyond reproach. Smaller facilities may not experience this level of pressure.

Additionally, people often believe that those who end up arrested did so due to their own poor choices, and they should suffer the consequences. Addictions come with a great deal of stigma, and people don’t always understand that addictions form due to chemical changes, not personal failings. Until that stigma fades, it’s possible that people will continue to see long stints in jail or prison with no treatment as a just punishment for a drug crime.

Life After Prison Release

For people serving time, it may seem like the sentence will never end. But sentences for simple crimes often come with shorter time requirements, and that means people who are convicted are often released at some point.

The National Reentry Resource Center reports that during 2015, 641,100 people sentenced to serve time in state or federal prisons were released to their own communities. That reentry point may be joyful, but it comes with specific dangers.

Prisons and jails are sterile environments, unfamiliar to people who have never been asked to live in them. Incarceration allows people who have addictions to step away from their lives, their pressures, and their habits. They are forced to renew themselves completely in a very different space. When they head home, they encounter their old lives, which may be tainted by abuse.

Returning home can be an incredible shock to someone who has just emerged from incarceration. Family members may have changed due to the pressures caused by a family member behind bars. The family may have endured financial losses due to the incarceration, and beloved belongings may be missing due to the need for money. Some family members may be gone altogether due to disease or relocation.

Returning to the community can also mean dealing with the reality verses the memory. While people are incarcerated, they may have fantasized what the return to home might look, sound, and feel like. When the reality doesn’t match those expectations, it can be a crushing blow or even a shock. For people with addiction, a shock is sometimes handled with a relapse. That relapse can be deadly.

During active addiction, people flood their bodies with substances of abuse. They need to take larger and larger doses to get the euphoric feelings that once came with smaller doses. Their bodies have adjusted to the impact of drugs. During sobriety, that damage is slowly undone and the body loses tolerance for the drug of choice.

Someone newly emerging from jail or prison may not take this into account, and during a relapse, the person may take an old and familiar dose of a drug. That old dose is just too high for the newly healed body, and an overdose can occur.

A researcher quoted in an article by Vox says that the first 2–6 weeks after release is the most dangerous time for overdose. This is the time in which people feel the most stress, and it’s the time in which their bodies are most unprepared for a return to drugs.

The solution might involve supportive counseling after release, but people who have spent years in prison may not have health insurance or the funds required to pay for care out of pocket. If they haven’t gotten treatment while incarcerated, they may not see the need to get treatment after release. For some, picking up the habit just seems reasonable.

Rehab Instead of Jail Time

The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) reports that people who get treatment due to some kind of legal pressure tend to keep their treatment appointments more frequently than people who are not under legal pressure, and they tend to stay in treatment for longer periods of time.

People who know they must achieve sobriety or face some kind of legal deterrent, including longer sentences or more strict incarceration levels, tend to take the treatment mandate seriously. That doesn’t mean, however, that the treatment must be provided in a prison or a jail.

There are treatment programs created specifically for people with addictions who are facing legal action. These programs might come with compliance measures, so those monitoring the case can ensure that the person is following the rules. Those compliance measures might involve mandatory enrollment in an inpatient program, or they could involve other monitoring steps, such as:

During the program itself, people might access medical detox services, so they can achieve sobriety in a safe and structured way. They might participate in counseling sessions, so they can learn more about the triggers that spur drug use and coping skills that can allow people to move past their triggers. They might spend time in support group meetings, learning more from other people who have addictions. These programs might also involve a work or schooling component, so people have busy lives that leave little room for buying or taking drugs.

A structured program like this can be remarkably effective. As NIDA suggests, most people who have extended treatment for addiction stop abusing substances in time, they stop breaking the law, and they start to become fully integrated and helpful members of society. Programs like this work.

But people who participate in these programs while not incarcerated need to develop a protective bubble to avoid common relapse triggers. For example, an article in Psychology Today reports that a common relapse trigger is spending time with former drinking or using buddies. Visiting places where the person used to buy or use drugs is another trigger.

People who are incarcerated face no such triggers. They cannot mix freely with people who aren’t incarcerated in the same facility, and they cannot leave the grounds to visit any place they’d like. Their choices are very limited, and in some cases, those limited choices help to protect them against relapses.

To truly succeed in a treatment program, this risk must be addressed through counseling, peer support, or both.

Learn More About Addiction Treatment

- Substance Abuse Treatment Center in Mississippi

- Medical Detox Centers

- Inpatient Treatment Centers

- Outpatient Rehab Centers

Comparing Rehabilitation vs. Incarceration

When looking at two different treatment modalities in order to determine which works better for people in need, it’s common to look at relapse rates. The fewer people who return to a substance of abuse, the thinking goes, the more effective the treatment must be.

This kind of thinking minimizes the very real impact of an addiction. As NIDA points out, addictions are diseases of brain chemistry. They are chronic conditions that can be managed very effectively, but the chemistry issue may always persist. As a result, a relapse to addiction isn’t just possible—it’s likely. Every person who has an addiction, even if that addiction is treated, is likely to face relapse.

It’s helpful to consider how the two spaces hold different pros and cons of rehabilitation in the criminal justice system.

Anyone who steps away from home to deal with an addiction, either through incarceration or through inpatient care, may have to deal with a difficult return home and its challenges. As an article in The Guardian makes clear, even people who walk away for just a month to deal with an addiction can return as different people with different habits and skills. In this piece, the couple’s arguments they once blamed on alcohol remained when one partner was sober. The couple didn’t know how to deal with those arguments during intoxication. They didn’t know how to deal with them in sobriety either.

When faced with the same scenarios in which the addiction flourished, including the same interpersonal challenges, adjustments are required. For some, an adjustment could lead to a relapse.

Incarceration can, and often does, come with release support. People who are released are often required to check in with case managers and outline the steps they’re taking to rebuild their lives after incarceration. While case managers are certainly not counselors who specialize in addiction, they are professionals who are trained to help people develop healthy habits. They offer support that can help make the return to normal life easier.

But that same role could be played with outpatient addiction care. Here, people meet with trained mental health professionals in a series of appointments, rather than living fulltime in an addiction treatment center, and they discuss how well they’re handling the addiction. The benefit is that the person would be talking with someone who knows about addiction and is trying to help them recover. Meetings can also be set up at a frequency the person needs, not one the court mandates, so it could provide better wraparound care.

People in recovery are urged to look for ways to build a healthy and active life, and that remains true whether they’re emerging from prison or a formal treatment program. Unfortunately, there are some unique challenges people face after prison release that could make an active life harder to build.

People in recovery are urged to look for ways to build a healthy and active life, and that remains true whether they’re emerging from prison or a formal treatment program. Unfortunately, there are some unique challenges people face after prison release that could make an active life harder to build.

The NAACP reports that a criminal record can reduce the likelihood of a job offer or job callback by close to 50%. That means people emerging from prison may find it hard to get the jobs they need to support their families, and the pressure they might feel due to poverty could be a major trigger for relapse. Financial woes could even push some people to return to dealing drugs.

Some of the things that happen in prison can also leave lasting scars that impede recovery. Some people feel as though they were incarcerated unjustly, while others may have endured physical assault while in prison. Those deep wounds can also work as relapse triggers, especially if they’re not addressed in therapy. These aren’t risks people face if they do not end up in prison or jail.

How to Prepare for Prison

While it might be interesting to compare the success of treatment in the community or in prison, people facing drug charges often don’t have a choice of treatment locations. They are charged, the courts make a decision, and they go where they are told to go.

Heading to prison can be a terrifying idea for anyone, and sometimes, there is little or no time to prepare for the experience. But people who have long court cases and extended sentencing can get themselves ready both physically and emotionally for incarceration. Experts suggest these steps.

For people with addictions, it can be tempting to prepare for prison with one last blowout of alcohol, drugs, or both. Prisons typically don’t allow these substances, and it can seem appealing to use them while the person still can. This is a terrible idea.

When used at high doses, addictive substances can cause very serious health challenges, including death. Continued use can lead to the need for medical detox, which some incarceration facilities don’t offer. Heading to prison or jail while intoxicated could also lead to additional charges if the substances used are considered illegal.

There is no harm in saying farewell to family members and loved ones, but keeping that celebration sober is the best way to ensure that the party doesn’t cause more misery.

Zoukis Prisoner Resources suggests digging into the policies and procedures of the prison the person will be sent to. That is especially important for people with addictions to alcohol or opioids. These people may need intensive medical detox in order to get sober, and if the prison does not offer those services, it would be wise for the person to get medical detox in the community before the sentence is due to start. It is also helpful to understand if the prison offers any kind of addiction support counseling and what methods are used. That can help people know what to expect from the treatment they may receive.

The Children with Incarcerated Parents Initiative suggests meeting with a doctor before checking into the prison. People with addictions may be taking a variety of medications in the early stages of recovery, and those medications may be used to soothe physical and mental signals of distress. While people are not allowed to take medications with them into the facility, having a prescription from a doctor on the doctor’s letterhead could be a useful way to demonstrate to the staff that the medications are required.

Mother Jones recommends working on the ego. People under pressure and stress may act proud and aggressive in order to mask their pain, but aggression and prison tend to bring about disastrous results. Remembering that the sentence will pass can help.

A study in the journal City also suggests that men might be more prepared for prison than they thought. Schools can be full of bullying behavior, and they often involve very strict rules followed by people who aren’t all that interested in following rules. Remembering that a situation like school has been survived before could help people to cope during dark days.

To help prepare for sobriety after release, people can talk to their dealers, their drug-using friends, and other peers to tell them that they’re entering prison and plan to emerge sober. These talks could help those abusing peers to see the very real consequences of addiction, and that could help them to consider sobriety as well.

Finally, it’s never a bad idea to meet with a counselor to discuss addiction and recovery. Even one or two sessions before the incarceration begins could help to bring about insights that can be nurtured and built on while in prison. Some counselors may be open to trading letters to discuss insights, and others may be willing to suggest books and other printed resources that could be accessed through the prison library. Getting that foundation of support now before the sentence begins could be lifesaving.

Recovery Is the Best Choice

Addictions are not rational. People who are dealing with the brain chemistry changes an addiction can cause may not be capable of understanding the very real consequences they may face if their abuse continues.

But addictions also occur on a spectrum. Some people have very severe symptoms, while others simply do not. People who abuse drugs now may be swayed to stop that use and abuse if they consider what life in prison might be like. They may also be swayed by messages of love and support by family members they trust.

Isolating the addicted person is not the answer. Speaking up and out matters more. Keep the conversation going despite what the addicted person might say. Treatment works. They just need to get it.

Take your next step toward recovery:

✔ Learn more about our addiction treatment programs.

✔ See how popular insurance providers such as Aetna or Humana offer coverage for rehab.

✔ View photos of our facility.